Shaping the future of humanoid robotics

Humanoid robotics has moved from academic prototypes to early real-world deployments. What once lived in journals and sci-fi is edging into factories, clinics and service work. Improvements in AI algorithms, sensors, power electronics and standardised components – alongside falling component costs – are enabling robots that can perceive, plan and act more like skilled tools than scripted machines.

This article draws on a recent Siemens × TUM (Technical University of Munich) roundtable on humanoid robotics, where two leading voices from academia and industry – Dr Georg von Wichert (Siemens) and Professor Gordon Cheng (TUM) – spoke about how technology and humanity are converging in the era of Physical AI. Both have been shaping the robotic field for decades.

What’s changing: from mechanics to cognition

Early iterations of humanoid robot research focused mainly on mechanics and low-level control, demonstrating individual capabilities. Progress was constrained by high costs and limited component availability. Today, the picture is shifting. Advances in actuators, sensors, power electronics and scalable software stacks have accelerated development and made robotics more accessible.

Said Gordon: “Sensors keep evolving…as well as software. Every day you hear something new in AI.”

Georg underscored how direct or semi-direct drives and modern power electronics make joint behavior increasingly software-defined, raising the ceiling for compliant, agile motion.

Modern humanoids combine perception, motion control and decision-making in integrated systems. This shift marks the transition from classical automation – rigid, scripted behaviors – to physical AI, where machines can process data, adapt policies and improve with experience.

As hardware becomes more standardised and commoditised, system intelligence and integration quality – beyond raw mechanics – are becoming the primary driver of progress. At the same time, vision- and language-powered open-world semantics are unlocking transfer across environments, while a ‘missing middle’ remains between high-level reasoning and robust, adaptable skills on real hardware.

Bridging the gap between simulation and reality

Physical experiments are time-consuming, and training data is often scarce. Robotics simulation allows researchers and engineers to prototype behaviours, validate design ideas and build ‘what-if’ scenarios in a virtual environment before turning on a real robot. This accelerates iteration and makes trials more repeatable and safer.

In practice, the simulation-reality gap is still significant: today’s engines still struggle with contact-rich physics (e.g., slippery objects, changing friction, soft materials). Sensor realism is also not perfect: simulated camera images may look great to humans but still be far from what a real camera would deliver.

As a result, policies that appear robust in the laboratory may lose their effectiveness with real robots. There are some underused levers: stronger domain randomisation, better system identification, more computing power for simulation accuracy and disciplined real-world validation, but there’s still a long way to go.

Towards human-centric and general-purpose robotics

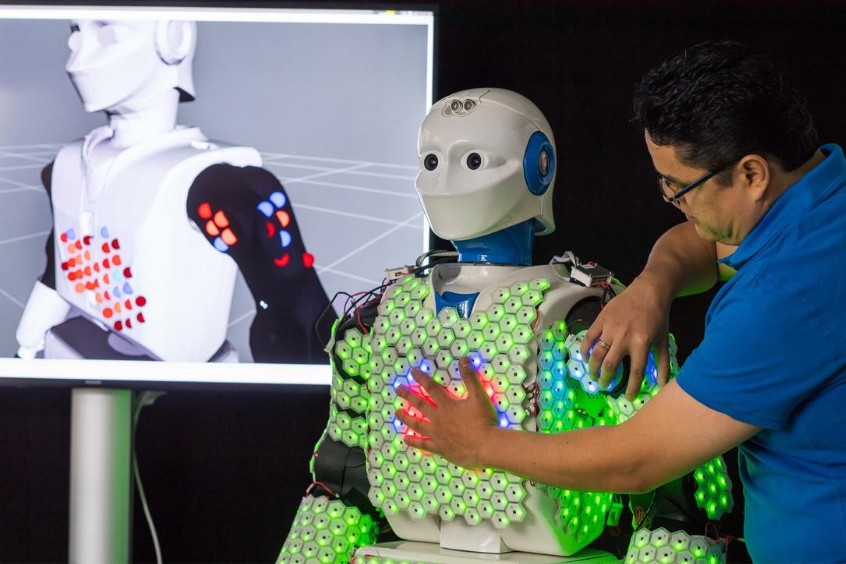

Achieving general-purpose capability demands more than precise motion. Robots must recognise intent, communicate with humans and operate safely with purposeful contact – especially in homes and healthcare.

Gordon argued we should let robots “make contact… and make it safe,” while Georg pointed back to the original idea of embodied intelligence: morphology, materials, sensing and control co-create capability. Actuators and compliant mechanisms remain under-invested frontiers compared with software.

Today’s humanoids still lack a robust mid-layer between high-level reasoning and low-level control. Robots can plan and they can stabilise, but they struggle to turn purpose into adaptable skills that hold up under real-world variability. Robot-native foundation models and contact-competent hardware/control are advancing but are not yet mature. Until then, specialised automation remains the most effective option where tasks are tightly constrained; while humanoids make sense in human-designed, variable or hazardousenvironments, truly general-purpose robots are not there yet.

Above all, robotic systems should be human-centric. Future humanoids should feel like ‘clothing-like’ exoskeletons – easy to put on, comfortable for daily use and under the user’s control – so they help people feel less dependent, not more. Human-centric also means preserving dignity and agency. In Gordon’s clinical research project, a patient insisted: “I don’t want this automated; I want to be in control.”

A future built on collaboration

The field of humanoid robotics is rapidly advancing, driven by increasingly close collaboration between academia and industry.

To further this synergy, Siemens and TUM have expanded their collaboration, establishing the Siemens Technology Center (STC) on TUM Campus Garching. This STC, which serves as Siemens’ largest global research hub, is designed as an open collaboration space to link academic excellence with robust industrial validation. STC aims to enable shared testbeds, joint datasets and faster lab-to-factory translation for robotic and autonomous systems, accelerating the path from concept to dependable deployment.

Beyond industry, this endeavour must also foster a strong collaboration between science and society. As humanoids enter homes, clinics and public spaces, there’s a critical need for trusted voices who can demystify the technology. Gordon and Georg have been at the forefront of this effort, engaging the public through public talks, clinical collaborations and open forums to translate complex techniques into clear, accessible language for diverse audiences.